Vascular trauma

ASPIRE Trauma 2024 - Draft Programme

Introduction

In England it is estimated that there are approximately 20,000 cases of major trauma annually, resulting in approximately 5,400 deaths.

Major trauma is the leading cause of death in patients <45 years. Vascular trauma arises from a variety of causes:

- Blunt injury from road traffic collisions (RTCs) - the most common cause in the UK.

- Penetrating and blast injury in conflict zones (and recently civilian terrorist attacks)

- Falls from height

- Iatrogenic injury from invasive medical procedures

Non-compressible truncal haemorrhage (NCTH) accounts for the highest number of preventable deaths in this group. Unless rapidly controlled it is followed by the lethal triad of shock, hypothermia, and coagulopathy. Successful management is dependent on a well organised, coordinated and systematic approach central to which is the necessity to control major bleeding rapidly.

Pre-hospital care and rapid transport to a trauma centre are key components of success. Where possible haemorrhage is controlled (i.e., tourniquet for extremity trauma, pelvic binder for pelvic fracture), oxygen given, and resuscitation commenced. Definitive haemorrhage control can then be achieved using surgical (damage control) and endovascular techniques (baloon occlusion and/or embolisation).

Triage

Triage describes the process of sorting casualties into categories for priority for treatment, with the aim of providing the greatest benefit to the largest number. A systematic approach is essential, using interpretation of established guidance from

The mechanism of injury (MOI) and primary survey form the basis of care for all trauma patients.

The MOI and pre-hospital treatment given are communicated using the ATMIST pre-alert.

- AGE (INCLUDING PATIENT NAME IF KNOWN)

- TIME OF INCIDENT

- MECHANISM

- INJURIES

- SIGNS – VITAL SIGNS

- TREATMENT GIVEN / IMMEDIATE NEEDS

ETA, mode of transport (land vs air), specialist resources required on arrival?

|

Emergency Department

Patient should be received by the trauma team in ED resus. A vascular surgeon will only be present in most EDs if their specialist input is required.

- Continue goal-directed, haemostatic control and resuscitation.

- Analgesia and relief of anxiety

- Trauma CT scan - rapidly identifies sites of chest, abdominal or pelvic bleeding.

Aim is for this to take place within 15 minutes of poly-trauma arrival in the ED and 30 minutes of arrival for isolated injury (to reduce ischaemic time).

- Antibiotics, urinary catheter, arterial lines, tetanus and pregnancy test.

- Speak to relatives

- Documentation

- Debrief

Tranexamic acid

Bleeding after vascular trauma is exacerbated by increased fibrinolytic activity. The CRASH-2 trial assessed use of tranexamic acid (TXA) in haemorrhagic shock after trauma in adults. If given within 3 hours of injury, a TXA 1g over ten minutes followed by a 1g infusion over 8 hours, significantly reduced all-cause mortality and death due to haemorrhage. TXA use is recommended within 3 hours of severe traumatic internal or external haemorrhage unless contraindication (i.e., past anaphylaxis).

Clinicians must be aware that whilst this use of TXA is supported by national JRCALC and local guidelines it is an off-label indication.

Major haemorrhage

- Hypotension out of proportion to injury suggests a major vascular injury.

- Blood loss is evidenced by BP (S) < 90 mmHg or heart rate > 90 bpm.

Massive haemorrhage is the pre-eminent cause of preventable death.

Major haemorrhage is defined as any of the following:

- Actual/anticipated requirement > 4 units RBC in 1 hour with ongoing transfusion

- > 1500mL blood loss in one episode with or without haemodynamic instability

- New cardiovascular instability considered to be related to acute haemorrhage

- 1 – 1.5 blood volumes may need to be transfused acutely or within a 24-hour period

Lost blood should be replaced with body temperature matched-solution oxygen-carrying and clotting capacity, and as such must include Red Blood Cells (RBC), Fresh-Frozen Plasma (FFP) and Platelets (PLT).

Meta-analyses of observational studies in trauma patients with massive haemorrhage have shown significant survival benefit in patients receiving high FFP/RBC and PLT/RBC ratios. Initial resuscitation is guided using a best guess estimation but likely with a 1:1:1 approach:

Permissive hypotension

A century ago, Walter Cannon stated that “inaccessible or uncontrolled sources of blood loss should not be treated with intravenous fluids until the time of surgical control”. Normotensive patients should receive no fluid resuscitation, whereas hypotensive patients should have fluid resuscitation withheld until systolic blood pressure approaches 80 mm Hg systolic, at which point careful, small-volume boluses of blood or plasma (250 to 500 ml) should be given to maintain systolic blood pressure between 80 and 90 mm Hg.

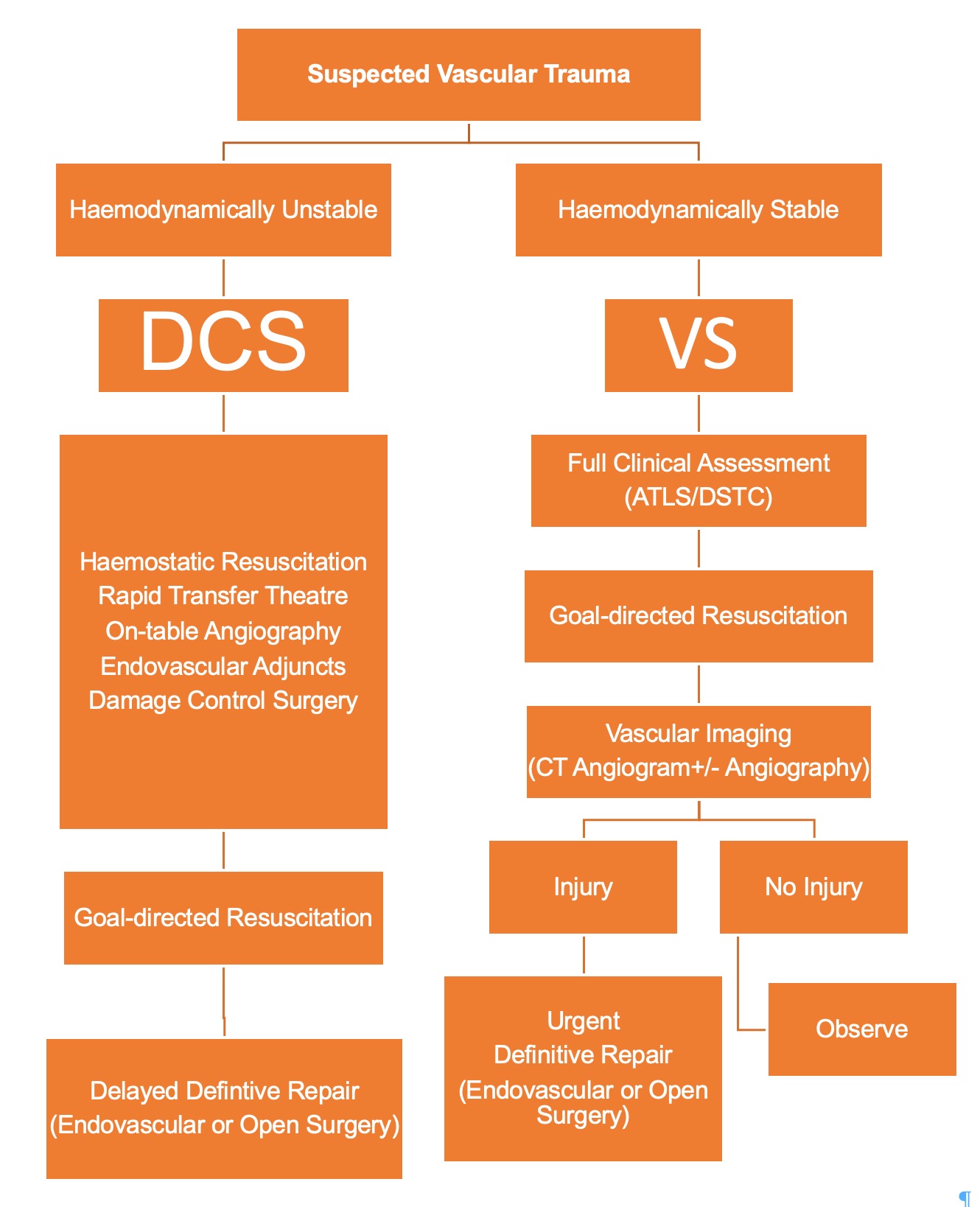

Damage-control surgery in poly-trauma or Definitive repair in isolated trauma.

Resuscitative thoracotomy

The indications for resuscitative thoracotomy in the Emergency Department are:

- Penetrating wound that could involve the heart AND has been in cardiac arrest (any rhythm) for less than 15 mins loss of output

- Traumatic cardiac arrest (for less than 10 mins) secondary to hypovolaemia from abdominal or pelvic haemorrhage - for proximal vascular control

The aim is to open the pericardium within 2 minutes of making the decision to proceed.

Urgent cardiac referral is indicated as soon as the decision is made to proceed to thoracotomy.

Resuscitative thoracotomy

External chest compressions are ineffective in this context and should not hamper the procedure.

Rapid application of chlorhexidine and open ‘TTL thoracotomy’ set.

Bilateral thoracostomies (3-5 cm each) should be performed axillary line just above 5th rib.

Internal cardiac massage: A two-handed technique is preferred. One hand is slid behind the heart, keeping it flat, and the other placed on top. Blood is ‘milked’ from the apex upwards at a rate of approximately 80 bpm. Ensure that the heart remains horizontal during massage. Lifting the apex of the heart too far out of the chest causes kinking of the great vessels and prevents venous filling. An assistant should compress the aorta against the spinal column using a hand placed posterior to the left lung to maximise coronary and cerebral blood flow.

Control of abdominal-pelvic bleeding: An assistant should compress the aorta against the spinal column using a hand placed posterior to the left lung until formal control is achieved with an aortic cross-clamp.

Control of cardiac injury: Holes less than 1 cm can usually be occluded temporarily using a finger or gauze swab. If this is successful, no other method should be attempted before the arrival of the cardiac surgeon. If bleeding cannot be controlled with finger/gauze compression it may be necessary to close the defect with large sutures (vertical mattress with 2/0 Vicryl) or skin staples taking care to avoid the coronary arteries that are normally fairly visible.

Chest drain

A haemothorax is a collection of blood in the pleural space, most commonly caused by rib fractures, lung. parenchymal injury or injuries to veins and (less commonly) arteries. In the absence of suspected spinal injury, patients with penetrating chest injuries should have an erect chest x-ray as an adjunct to the primary survey. As well as revealing pneumothoraces and rib fractures, it may show a fluid meniscus which would indicate at least 500mls of blood loss has occurred.

Chest drain

Chest drain; this must be at least 32Fr and preferably 36Fr to avoid clot blockages.

Insert wide bore IV access prior to drainage and consider adjuncts such as cell salvage devices – large volume blood loss should be anticipated.

Major vascular Injury

A strong correlation has been noted between increasing severity of injury and incidence of associated vascular injury. A major vascular injury should be suspected in anyone with signs of significant blood loss; control of haemorrhage is the priority.

Circulatory compromise secondary to displaced, angulated long bone fractures and / or joint dislocation e.g. mid shaft femoral or supracondylar humeral fracture should have the injury realigned or relocated as quickly as possible. A normal ankle brachial pressure index of >0.9 and the absence of hard signs of arterial injury effectively excludes the possibility of an arterial injury.

With extremity injuries, signs may be frank from the outset, but in the cavities of chest or abdomen, signs may be subtle, and must be actively sought.

BOAST: Arterial injuries associated with extremity fractures and dislocations (2.1)

| Hard signs |

Soft signs |

|

Pulsatile bleeding

Expanding haematoma

Absent distal pulses

Cold, pale limb

Palpable thrill

Audible bruit |

Haematoma (small)

History of haemorrhage at scene

Unexplained hypotension

Unexplained tachycardia

Peripheral nerve deficit |

Patients with hard signs of vascular injury require surgical intervention in over 95% of cases.

Damage Control Surgery

This approach prioritizes the control of haemorrhage and contamination on initial surgical intervention and involves leaving the abdominal cavity with a temporary closure and delaying definitive surgical reconstructions for subsequent operations. Between stages patients are managed on the intensive care unit. Its adoption directly mitigates the vicious cycle of hypothermia, acidosis and coagulopathy.

Compartment Syndrome

Bleeding into a compartment, soft tissue blunt trauma, blast injury and ischaemia reperfusion can all result in raised compartment pressures and secondary damage to muscles and nerves. Fasciotomies can prevent compartment syndrome and should be considered if there are major associated injuries (i.e., bone, soft tissue), crush injuries, associated venous injury, or if ischaemia is prolonged (greater than six hours).

Acute compartment syndrome of a limb is due to raised pressure within a closed fascial compartment causing local tissue ischaemia and hypoxia. Assessment for compartment syndrome must be routine in trauma patients with:

- Significant limb injuries, including major vascular injury, forearm fractures, high energy injuries and crush injuries.

- Prolonged pre-hospital tourniquet application.

- After any prolonged surgical procedure which may result in hypoperfusion of a limb OR delayed reperfusion.

Key clinical findings are pain out of proportion to the associated injury and pain on passive movement of the muscles of the involved compartments. Limb perfusion, including capillary refill and pulses, do not aid early diagnosis, as pulses are normally present.

Ward based management

Hourly limb observations for compartment syndrome. Regional anaesthesia should be avoided as it can mask the symptoms of compartment syndrome. Patient-controlled analgesia with intravenous opiates can also mask the symptoms.

Patients with symptoms or signs of compartment syndrome should have all circumferential dressings released and the limb elevated to heart level. Measures should be taken to maintain a normal blood pressure. Patients should be re-evaluated within 30 minutes. If symptoms persist then urgent surgical decompression should be performed.

Compartment pressures

Measuring compartment pressures at multiple sites may be of benefit in equivocal cases. A difference between diastolic blood pressure and the compartment pressure of < 30 mmHg suggests an increased risk of compartment syndrome. If the absolute compartment pressure is > 40mmHg, with clinical symptoms, urgent surgical decompression should be considered unless there are other life-threatening conditions that take priority

When in doubt it is safer to perform fasciotomies.

Fasciotomy

Compartment syndrome is a surgical emergency and surgery should occur within 1 hour of the decision to operate. Surgery should involve open fascial decompression of all involved compartments, taking into account possible reconstructive options. Necrotic muscle should be excised. The compartments decompressed must be documented in the operation record.

All patients should undergo re-exploration at approximately 48 hours, or earlier if clinically indicated. Early involvement by a plastic surgeon may be required to achieve appropriate soft tissue coverage.

Non-viable to Non-functional limb

Certain limb injuries are so severe that functional limb salvage would appear futile. Consideration should be given to primary amputation of severely injured extremities, especially in unstable patients with multi-system injuries, and can rapidly be achieved by guillotine or standard approaches.

The Mangled Extremity Severity Score (MESS) estimates the likelihood of an amputation being necessary. A score of seven or more almost always requires an amputation.